19 May GOTTA READ ‘EM ALL, BOOK 2: PRIDE AND PREJUDICE BY JANE AUSTEN

My quest to conquer my to-be-read list continued this week with the second book in the pile, Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen. It was not a book I was looking forward to. It’s a capital-C Classic, which in terms of the English novel tends to mean bonnets, posh people worrying about their yearly income, ‘a chill’ being a deadly illness, a brooding male lead, and two-hundred year old satire which has unsurprisingly failed to stand the test of time. None of which I find particularly interesting; a hangover, I think, from being made to read Jane Eyre for A Level.

Pride and Prejudice is centred around the five Bennet sisters, particularly Elizabeth, the second-eldest. When Mr Bingley, an eligible bachelor, moves in to a neighbouring country house, the sisters are pushed into his circle by their mother, who is desperate to marry them off. Elizabeth can’t stand Bingley’s aloof, morose best friend, Fitzwilliam Darcy, which pretty much tells you all you need to know about what will happen to the pair of them.

One of the hardest things to get to grips with when reading Pride and Prejudice is how familiar it all feels. Although I’d never read it, many of the main cast were already well known to me, as well as most of the plot: I’d seen both the 1940 film starring Laurence Olivier and the more recent Keira Knightley version; I’d watched Lost in Austen, the ITV drama where an avid fan of the book wakes up to find herself inside it; and I’d even seen what happens when you add the undead to the mix in the wonderfully titled Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Even if I hadn’t, I think it would be difficult to have an interest in culture and not know something of the characters and plot. All of which meant I often found myself waiting for things to happen way before they did: I knew Wickham was a cad, so found Lizzie’s almost-romance with him tedious. Darcy and Lizzie’s romance is now legendary, so waiting three hundred pages for it to happen was not the greatest reading experience.

One of the hardest things to get to grips with when reading Pride and Prejudice is how familiar it all feels. Although I’d never read it, many of the main cast were already well known to me, as well as most of the plot: I’d seen both the 1940 film starring Laurence Olivier and the more recent Keira Knightley version; I’d watched Lost in Austen, the ITV drama where an avid fan of the book wakes up to find herself inside it; and I’d even seen what happens when you add the undead to the mix in the wonderfully titled Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Even if I hadn’t, I think it would be difficult to have an interest in culture and not know something of the characters and plot. All of which meant I often found myself waiting for things to happen way before they did: I knew Wickham was a cad, so found Lizzie’s almost-romance with him tedious. Darcy and Lizzie’s romance is now legendary, so waiting three hundred pages for it to happen was not the greatest reading experience.

None of this is the fault of the book, of course. When Jane Austen was writing it, she’d’ve never imagined we’d still be reading two centuries later, let alone that people would know it without ever picking up a copy. But still, the parts I liked the best were those that can’t be replicated in adaptations. The narrator – or, if you prefer, Austen’s narrative voice – is easily my favourite character. She’s sharp and funny, but sly with it; nicely understated, and unafraid to mock our supposed heroes: Lizzie is often unbearably self-important and delusional (both the pride and prejudice of the title come from her), and Austen doesn’t mind gently pointing this out. Conversely, when it comes to the broader, more obviously comic characters – Mr. Collins, Mrs. Bennet – Austen allows them moments of empathy so we understand them as we laugh at them. She does this by moving the point of view between characters, but crucially excluding Darcy until the moment he and Lizzie proclaim their love towards the end. It keeps him remote from us until he is proposing, sweeping us up in the romance of the moment: we know Lizzie’s feelings at this point, and have done for some time. It’s the perfect place to let us see the world from Darcy’s head, if only briefly.

I think this is ultimately why the book has stood the test of time, and why the various adaptations do it an injustice. It is difficult to portray the characters as fully and well rounded as they are here in the confines of a film or television series, because Austen lets us dislike them as much as we like them. Dramas – and actors – that let us do this are few and far between, and are mostly a modern phenomenon. (Though I have to say, I doubt there has been a better Mr. and Mrs. Bennet than Hugh Bonneville and Alex Kingston in Lost in Austen. Likewise, has there ever been anyone more perfect for Mr. Collins than Pride and Prejudice and Zombies‘ Matt Smith? Interesting that these performances are to be found in work inspired by the book, rather than directly adapted from it.)

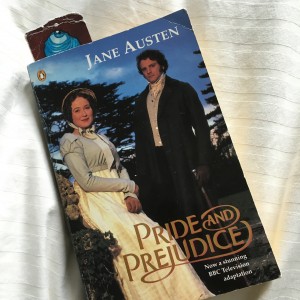

My copy is, strangely for a book that is over two hundred years old, one of the most nineties objects in existence. It’s a tie-in published at the time of the 1995 BBC adaptation, and so a very young looking Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle grace the cover. The price is £2.99 – amazing to think books were ever so cheap – and the back cover advertises the release of the VHS. The fonts and design are really dated, and have an almost homemade feel. In fact, I imagine knocking up a better quality cover in Photoshop would take little more than an hour. I bought it in 1995 as a Christmas present for my mum, who’d been watching the TV show. (The book was more within my teenage budget than the VHS, I imagine). I found it at her house last year, and resolved to read it. The spine remained uncracked until I opened it two weeks ago, so it reading it was a weirdly retro experience. And says a lot about how good I was at picking presents twenty years ago.

My copy is, strangely for a book that is over two hundred years old, one of the most nineties objects in existence. It’s a tie-in published at the time of the 1995 BBC adaptation, and so a very young looking Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle grace the cover. The price is £2.99 – amazing to think books were ever so cheap – and the back cover advertises the release of the VHS. The fonts and design are really dated, and have an almost homemade feel. In fact, I imagine knocking up a better quality cover in Photoshop would take little more than an hour. I bought it in 1995 as a Christmas present for my mum, who’d been watching the TV show. (The book was more within my teenage budget than the VHS, I imagine). I found it at her house last year, and resolved to read it. The spine remained uncracked until I opened it two weeks ago, so it reading it was a weirdly retro experience. And says a lot about how good I was at picking presents twenty years ago.

Keep or donate?

Keep. It’s not mine to give away! Plus, it’s a historical object – how can I let that go?

Next time, the BoD bookmark will take up residence in A Death at the Palace by M. H. Baylis. ‘Til next time: keep reading…

No Comments